On a foggy summer day in July 1917, multitudes of San Franciscans turned out to dedicate one of the city's most transformative public works projects- the Twin Peaks Tunnel. Two short miles of tunnel undercut the range of hills in the heart of the city that had essentially blocked westward expansion for years. This feat of engineering, and the streetcar lines that later ran in the tunnel, would propel the imminent neighborhoods around the tunnel’s West Portal, as well as Forest Hill, Stern Grove, Lake Merced, Parkside and St. Francis Wood into sudden growth and prosperity.

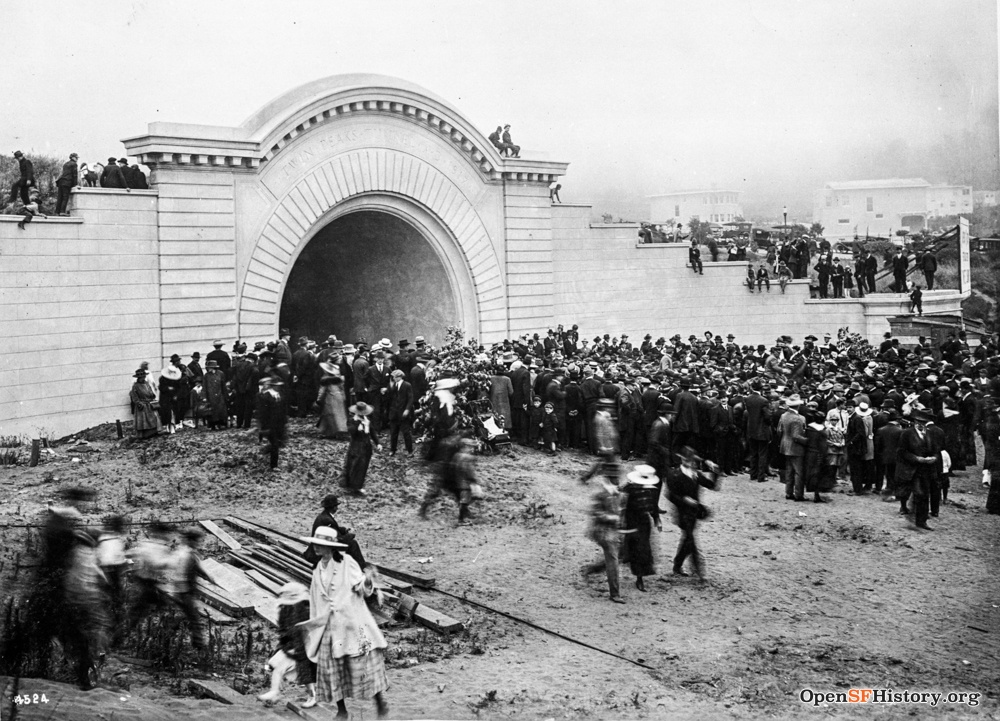

Crowds of people gathered at the then non-existent intersection of West Portal Ave and Ulloa Street to watch then Mayor James Rolph and City Engineer M.M. O'Shaughnessy drive a ceremonial spike to mark the completion of the bore on July 14, 1917. Photo courtesy OpenSFHistory / wnp36.01654.jpg.

Although two streetcar lines already reached the southwest area of the city by circuitous routes, access was difficult and slow and nearly 4,000 acres of land lay undeveloped. Public debate, studies and tunnel proposals started as early as 1908 but it wasn't until 1914 that the plans were finalized and money secured to build a streetcar tunnel under Twin Peaks and finally connect the area directly to downtown.

A small rail conveyor system was built to haul away excavated dirt on the eastern portion of the tunnel. This view looks east down Market Street near Diamond Street.

Construction of the tunnel required digging large, open trenches on both the east and west approaches to the main tunnel bore. Much of this trenching work was done with the aid of steam shovels while the more difficult portion underneath Twin Peaks was dug by hand with pick, shovel, and dynamite.

Following two and a half years of construction, the tunnel was complete by mid-1917 and the final pieces of streetcar infrastructure were laid in place later that year. In early 1918, Muni’s K Ingleside streetcar made its debut through the Beaux-Arts style façade of the West Portal of the Twin Peaks Tunnel to a crowd of cheering people.

Seen here in 1919 is the original archway of the West Portal of the Twin Peaks Tunnel. Within ten years of this photo being taken, the area started to look similar to today as houses and businesses sprouted up around the portal.

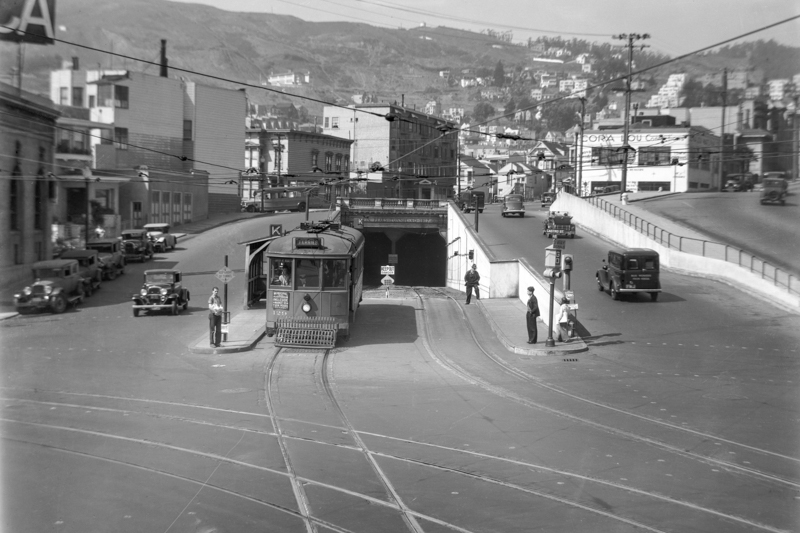

The East Portal of the Twin Peaks Tunnel in 1935 with a K Line streetcar at Market and Castro.

Prior to the creation of Muni Metro and its Market Street subway tunnel, the Twin Peaks Tunnel emerged heading towards downtown at its East Portal on Market at Castro, with streetcars continuing above ground. By the late 1970s, preparations for the new Muni Metro subway and Boeing light rail vehicles meant that both East and West Portals were reconstructed. West Portal was rebuilt into the station you see today with long, high-level platforms and Castro Station occupies the former East Portal location.

The new, larger West Portal station designed to work with Boeing light rail trains was dedicated on April of 1979, seen here around that time.

The tunnel continues to play an important role in the Muni rail system today. It carries about 80,000 customers daily on the K Ingleside, M Ocean View and L Taraval lines. In summer 2018, SFMTA will be replacing the tracks and making vital upgrades to the tunnel’s infrastructure to keep it going for years to come. More information about the project can be found on the Twin Peaks Tunnel Improvement Project page.

Coming up on Saturday, February 3rd, SFMTA will be celebrating the 100th anniversary of the opening of the K Ingleside line and the Twin Peaks Tunnel at the 2018 West Portal Library Open House. Stop by the library between 1 and 5 pm to check out our exhibit on the history of the tunnel and the K Ingleside as well as storytelling, smoothies and giveaways.

To see more images of the Twin Peaks Tunnel through the years check our photo archives at SFMTA Photo website, or find us on Instagram @sfmtaphoto.